News

12/2015:

Damages to Bosra Citadel (Syria) new!

10/2015: Consolidation works

at Crac des Chevaliers (Syria) new!

06/2015: Reopening of the

Ayyubid City Wall of Cairo (Egypt) new!

06/2015:

Reopening of

the Othello Tower/Citadel of Famagusta (Cyprus)

11/2014:

Damages to Ḥārim Castle (Syria)

10/2014: Restoration of the

Land Castle (Qal‘at al-Mu‘izz; Château de Saint-Louis) in

Sidon (Lebanon)

07/2014:

Restoration of the Crac des Chevaliers Castle (Syria)

04/2014:

Restoration of the Othello Tower/Citadel of Famagusta (Cyprus)

07/2013:

Damages to Crac des Chevaliers (Syria) due to Bombing

09/2012:

Excavations in the Castle of Silifke (Turkey)

07/2012: Excavation of the

Town Wall of Harran (Turkey)

07/2012:

Hoard of Gold Coins Found in Citadel of Arsūf (Israel)

05/2012:

Damage to Medieval Fortified Sites in Syria

11/2011:

West Gate of Melitene (Eski Malatya) Town Walls Restored (Turkey)

11/2011:

Arabic Crusader Inscription from Jaffa (Israel)

09/2011:

Yavneh-Yam/Mīnat Rūbīn (Israel)

05/2011: The Last Supper in

Apollonia (exhibition)

04/2011: The Battle at Vadum Iacob

(Israel)

01/2011:

Salamīya and Šumaymīs Castles (Syria)

10/2010: Haruniye/al-Hārūnīya/Haronia

Castle (Turkey)

08/2010: Beaufort Castle/Qal‘at

aš-Šaqīf (Lebanon)

12/2009: Saône Castle/Saladin’s

Castle/Qal‘at

Ṣahyūn/Qal‘at Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn (Syria)

11/2009: Beirut Citadel

(Lebanon)

09/2009: Margat Castle/Qal‘at

al-Marqab (Syria)

09/2009: Rumkale/Qal‘at

ar-Rūm/Hṙomgla Castle (Turkey)

08/2009: Balatunus

Castle/Qal‘at Maḥālba (Syria)

07/2009: Petra and Šawbak Castle

(exhibition)

05/2009: Antioch Gate (Bāb

Anṭākiya) and City Wall of Aleppo (Syria)

01/2009: Town Wall Fortification

at Jaffa (Israel)

12/2008: Citadel of Arsūf (Israel)

10/2008: Maṣyāf Castle (Syria)

03/2008: Montfort Castle Project

(Israel)

02/2008: City Wall of

Alexandria/al-Iskandarīya (Egypt)

12/2007: Sea Wall and Harbour

Fortress at Jaffa (Israel)

08/2007: Crusader City Wall at

Tiberias (Israel)

12/2015: Damages to Bosra Citadel (Syria)

The citadel of Bosra (Buṣrā aš-Šām), an important Islamic stronghold in the Hauran south of Damascus, was hit by barrel bombs during an attack on the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Bosra. The local community of Bosra had already reported minor damages in July this year. From the eleventh century onwards different Islamic rulers turned the 2nd-century Roman theater of the town into a mighty bulwark. Its strategic value became once more important when it was used by the Syrian army as a military base in the past years, which was lost to the Syrian rebels together with the town in March 2015. The reported damages comprise the collapse of walls of the citadel’s western tower, the crumbling of the pillars and a jamb of the south-western door of the nearby western portico, and destructions at the castle’s wastewater disposal system. Additionally, the second level of the passageway surrounding the theater was breached, blocking subjacent corridors with fallen stones.

References: Report

of

damages (Souriat.com, 22 Dec. 2015); English

report (Now., 23 Dec. 2015); Youtube report (Orient News, 23

Dec. 2015); Picture story (APSA); Report of earlier damages (DGAM)

Further reading: C. Yovitchitch, La

citadelle, in: J. Dentzer-Feydy, M. Vallerin, T.

Fournet, R. and A. Mukdad (eds), Bosra aux portes de l’Arabie, (Guides

archéologiques de l’Ifpo, 5) Beyrouth 2007, pp. 179-188; id., Bosra: Eine Zitadelle des Fürstentums

Damaskus, in: M. Piana (ed.), Burgen und Städte der

Kreuzzugszeit.

(Studien zur internationalen Architektur- und Kunstgeschichte, 65)

Petersberg 2008, pp. 169-177

Collapsed pillars and other

damages in the western portico (© Souriat.com)

Collapsed pillars and other

damages in the western portico (© Souriat.com) A bomb crater in

front of the entrance to the western tower (© Souriat.com)

A bomb crater in

front of the entrance to the western tower (© Souriat.com)10:2015: Consolidation works at Crac des Chevaliers (Syria)

The Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM) gave account of consolidation works at the Crac des Chevaliers and other sites during this year. They comprised structural measures at the so-called "Hall of the Knights", cleaning of its façades, and the re-alignment and re-positioning of stones there. However, a comprehensive restoration effort would be necessary to safeguard this UNESCO World Heritage Site. Further consolidation works were carried out at the citadel of Damascus, the citadels of Maḥālba, and the citadel of al-Ḫawābī.

Reference: Report (DGAM)

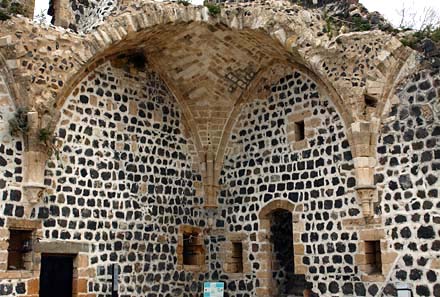

Stabilizing of arches at the vestibule of the

"Hall of the Knights"

Stabilizing of arches at the vestibule of the

"Hall of the Knights" Clearance works at the main ward

Clearance works at the main ward06/2015: Reopening of the Ayyubid City Wall of Cairo (Egypt)

In the framework of the al-Azhar Park Project, launched by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture in 1996, the Darasa hill was levelled, a dump of rubble for over 500 years beyond the eastern section of the Ayyubid city wall. This included the uncovering of the lower sections of the wall, which led to a further project in cooperation with the IFAO and Egyptian authorities concerning the investigation and restoration of Cairo’s city wall. It was launched in 2000 and comprised excavations as well as cleaning and restoration works at the city’s east wall. The excavations were concentrated on four main areas, the Bāb an-Naṣr (north wall), the Burǧ aẓ-Ẓafar (north-east corner), the Bāb al-Barqiyya, and the Bāb al-Maḥrūq (both east wall). With the help of references from literary sources, the chronological sequence of the Ayyubid wall and its relation to the three earlier Fatimid walls could be determined. The former was built in four stages, with the two earlier ones attributable to Saladin, who attempted to connect al-Qāhira with the newly-built citadel. His first measure, then as a vizier to the last caliph of the Fatimids, was to replace the parts of the Fatimid wall in brick by stone walls. From 1174 to 1178 he had new walls built from the Bāb al-Qanṭara at the north-west corner of al-Qāhira to the Burǧ al-Maḥrūq at the east side, where they were linked to the Fatimid south wall. The extension from here to the citadel was executed later, from 1192 to after 1200. The new walls, together with the citadel of Cairo, which was built from 1176 to 1183, constitute Saladin’s most ambitious fortification project during his reign as Sultan of Egypt.

Reference: Al-Ahram Weekly, 25 June 2015

Further reading: S. Pradines, Benjamin Michaudel, Julie Monchamp, La muraille ayyoubide du Caire : les

fouilles

archéologiques de Bāb al-Barqiyya et Bāb al-Maḥrūq,

in: Annales

Islamologiques 36 (2002), pp. 287-337

The north wall,

Ayyubid section east of Bāb an-Naṣr

The north wall,

Ayyubid section east of Bāb an-Naṣr Bāb al-Barqiyya

(573/1177-78) at the east wall during restoration works

Bāb al-Barqiyya

(573/1177-78) at the east wall during restoration works Burǧ al-Maḥrūq, the

southernmost point of Saladin’s wall

Burǧ al-Maḥrūq, the

southernmost point of Saladin’s wall The south section of the

east wall, built after 1178

The south section of the

east wall, built after 117806/2015: Reopening of the Othello Tower/Citadel of Famagusta (Cyprus)

The citadel of Famagusta, also called Othello Tower due to the fictional setting of Shakespeare’s play "Othello", will reopen on 2 July with a performance of the drama. The expenses for the restoration works, which were commissioned by the Cypriot Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage and funded by the European Commission and the United Nations Development Program Partnership for the Future (UNDP-PFF), added up to more than 1 million euros. The works had been necessary to protect the building against rainwater decay.

References: Greek reporter, 16 June 2015; Technical

Committe on Cultural Heritage project sheet

Further reading: C. Corvisier, Le château de Famagouste,

in: J.-B. De Vaivre, P. Plagnieux (eds), L’Art gothique en Chypre,

(Mémoires de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 34) Paris

2006, pp. 351-366; J. Petre, Crusader Castles of Cyprus. The

Fortifications of Cyprus under the Lusignans: 1191 – 1489,

(Texts and Studies in the History of Cyprus, 69) Nicosia 2012, pp.

153-164

The main gate of the castle during restoration

works

The main gate of the castle during restoration

works Deteriorated Lusignan coat of arms on a keystone

in the north wing

Deteriorated Lusignan coat of arms on a keystone

in the north wing11/2014: Damages to Ḥārim Castle (Syria)

The Syrian Directorate-General of Antiquities & Museums published a report on recent damages to the castle based on an assessment of the Idlib Antiquities Department. Few illegal excavations were observed, as well as fallen stone blocks causing gaps in the north and south walls, the removal of iron doors, except at the main entrance, and the blocking of postern gates. The castle was founded by the Byzantines after the taking of Antioch in 969. During the first half of the 12th century in Crusader hands, it was a bone of content between them and Nūr ad-Dīn in the following decades. From 1183 onwards it was occupied by the Ayyubids, substantially rebuilt by al-Malik aẓ-Ẓāhir Ġāzī of Aleppo in 1199. Twice attacked by the Mongols (1260 and 1271) and repaired at the beginning of the 14th century, the castle lost its military functions during the late Mamluk period to serve as a village.

Reference: Report

of damages (DGAM, November

2014)

Further reading: S. Gelichi, Il castello di Harim (Idlib-Siria).

Aggiornamenti sulla missione archeologica: la campagna di scavo 2000,

in: Le Missioni Archeologiche dell’Università di Ca’ Foscari di

Venezia. III giornata di Studio, Venezia 2002, pp. 76-85; id., The

Citadel of Harim, in: H. Kennedy (ed.), Muslim

Military Architecture in Greater Syria: From the Coming of Islam to the

Ottoman Empire, Leiden 2006, pp. 184-200

The ḥammām

inside the castle

in 2014 (© DGAM)

The ḥammām

inside the castle

in 2014 (© DGAM) The ḥammām

in 2002 in a less dilapidated state

The ḥammām

in 2002 in a less dilapidated state10/2014: Restoration of the Land Castle (Qal‘at al-Mu‘izz; Château de Saint-Louis) in Sidon (Lebanon)

Under the supervision of the municipality of Sidon and in cooperation with the Council for Development and Reconstruction together with the Ministry of Culture, a project was launched to renovate the long-neglected site. The aim of the measurements, wich are supported by a $849,000 grant from Italy, is to safeguard the town’s cultural heritage and to promote tourism, for which reason a touristic path is planned leading from the site to Sidon’s Sea Castle. The Land Castle, in fact the town’s citadel once incorporated into the south-east corner of the town wall, was founded in 975 on behalf of the Fatimid Caliph al-Mu‘izz li-Dīn Allāh on the site of a Late Roman theatre. The perimeter wall of the cavea, the outer wall of the stage building (scaena) and the two stair towers (versurae) at either side of which provided a perfect basis for the construction of a fortification. The town was in Crusader hands from 1110 until 1187, when it was taken over by Saladin who had razed its fortifications in 1190. Further demolition works are reported for 1196. Although again in Crusader hands 1229-49 and from 1250 onwards, the Land Castle seems to have been refortified only in June 1253 when an advance unit of King Louis’ IX forces began to rebuild the walls of the town and the citadel. They were, however, destroyed following a Mongol attack in 1260 and rebuilt not until the end of the 16th century, when the Druze Emir Faḫr ad-Dīn II had made the town the capital of his new empire. During later periods the site suffered damage from the deployment of troops (during the 18th century and in WW I) as well as from shelling (1941).

Reference: The Daily Star, 09 Oct. 2014

The

interior of the castle

in 2003

The

interior of the castle

in 2003 The

stage building (right)

with adjacent castle walls

The

stage building (right)

with adjacent castle walls07/2014: Restoration of the Crac des Chevaliers Castle (Syria)

The castle, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was retaken by government troops in March this year after having been under the control of Syrian opposition forces since July 2011. The fightings caused severe damages to the castle, which had been founded around 980. In Crusader hands from 1110 to 1271, it later served as a military base and an administrative centre by the Mamluks. The main fabric of the castle is the work of the Knights Hospitaller who had it completely rebuilt in the decades after the devastating earthquake of 1170. Its outer appearance is however marked by the rebuilding commissioned by Sultan Baybars following the conquest of 1271. The castle was inspected by a team of the Syrian Directorate-General of Antiquities & Museums who published a first report of the damages. Additionally, cleaning and emergency restoration works were carried out, as a first stage of the rehabilitation of the site. Further assessments are necessary to implement more comprehensive consolidation and reconstruction works which are planned for 2015. The damages comprise the destruction of the topmost vault at the SE tower of the main ward, the collapse of the staircase which once led from the inner courtyard to the roof of the southern hall range of the main ward, the loss of the tracery of the vestibule windows of the Knights’ Hall, and substantial losses of masonry at the Tower of Baybars.

References: First report of damages (DGAM, March 2014, with photos); Photographic documentation of damages (DGAM, March 2014); Report of works related to first phase of rehabilitation plan (DGAM, July 2014)

Damaged upper vault

of SE tower of main ward

after cleaning (© DGAM)

Damaged upper vault

of SE tower of main ward

after cleaning (© DGAM) Collapsed staircase at east side

of inner

courtyard (© DGAM)

Collapsed staircase at east side

of inner

courtyard (© DGAM) Vestibule of the

Knights’ Hall with lost window

tracery (© DGAM)

Vestibule of the

Knights’ Hall with lost window

tracery (© DGAM) Restoration works

at the Tower of Baybars (©

DGAM)

Restoration works

at the Tower of Baybars (©

DGAM)04/2014: Restoration of the Othello Tower/Citadel of Famagusta (Cyprus)

The castle called Othello Tower, in fact the citadel of Famagusta, was founded in the early 14th century by Amaury of Tyre, brother of the Lusignan King Henry II, to better protect the port of the city. In 1492 the Venetians had completely encased the former castrum-type fort with thick walls and huge bastions to adapt it to the requirements of current siege warfare. The restoration works, commissioned by the Cypriot Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage and funded by the EU, comprise stabilisation works, the implementation of a proper drainage system and new roof layers. The structural consolidation works are thought to be completed within eight months.

References: Technical

Committe on Cultural Heritage project sheet;

Al

Jazeera Report (Youtube video)

Further reading: C. Corvisier, Le château de Famagouste,

in: J.-B. De Vaivre, P. Plagnieux (eds), L’Art gothique en Chypre,

(Mémoires de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 34) Paris

2006, pp. 351-366; J. Petre, Crusader Castles of Cyprus. The

Fortifications of Cyprus under the Lusignans: 1191 – 1489,

(Texts and Studies in the History of Cyprus, 69) Nicosia 2012, pp.

153-164

The inner

ward of the citadel, from SE

The inner

ward of the citadel, from SE Vaulting

of the north wing, from

W: collapsed

rib and other damage

Vaulting

of the north wing, from

W: collapsed

rib and other damage07/2013: Damages to Crac des Chevaliers (Syria) due to Bombing

Bombings of the Crac de Chevaliers have hit the uppermost parts of both the south-east tower of the main ward and the former castle chapel. While at the chapel apparently only the coping of the walls was affected, at the south-east tower, by then preserved up to its upper defensive platform, the vault of the north room of the upper floor collapsed. Further, though minor, damages to other parts of the castle are reported. The castle was inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage Site List in 2006 and was added in 2013 to its World Heritage in Danger list, together with the other Syrian sites, due to the ongoing threat of damage in the country’s conflict.

Reference: Apsa2001.com; Photographic documentation of damages (Facebook page)

The collapsed

vault of the SE tower (© Apsa2011)

The collapsed

vault of the SE tower (© Apsa2011)09/2012: Excavations in the Castle of Silifke (Turkey)

During the excavations, which were headed by A. Boran from Selçuk University, the entire western section of the castle’s inner ward was exposed. The works revealed not only ground walls of buildings from the Ottoman period but also the remains of a mosque attributed by the 17th-century traveller Evliya Çelebi to Sultan Bayezid II. Moreover, cisterns were discovered which were already in use during the medieval period. The clearing works were already begun in 2011, starting from the western corner of the castle’s inner ward. Additionally, a sounding was carried out inside the gate tower at the central north side, which has been restored in the previous years, and the area between the tower and the castle’s main wall was cleared from rubble, revealing a walking path cut into the bedrock. Further measures comprised the removal of debris inside the great hall north of the western corner of the inner ward and in the ground floor chamber of the large horse-shoe tower south of it. The castle, originally a Byzantine outpost against Seljuks, Crusaders and Armenians, belonged to the Armenians from 1188 to the 14th century, with a Hospitaller interlude from 1210 until 1226. During the 15th century it was taken over by the Ottomans.

Reference: Silifke Kalesi Kazısı; A. Boran, 2011 Yılı Silifke Kalesi Kazı Çalışmaları. Excavations at Silifke Citadel, in: ANMED 10 (2012), pp. 99-102

W section

of inner ward from

W

W section

of inner ward from

W W section

of inner ward from SE

W section

of inner ward from SE Exposed

mouth of cistern in

W

section of

inner ward

Exposed

mouth of cistern in

W

section of

inner ward Exposed

passage between

forewall/gate tower (left) and main wall (right)

Exposed

passage between

forewall/gate tower (left) and main wall (right) Entrance

to NW hall showing level of

debris inside

Entrance

to NW hall showing level of

debris inside Interior

of NW hall from E

Interior

of NW hall from E07/2012: Excavation of the Town Wall of Harran (Turkey)

In the framework of a larger project to revive the historical remnants of Harran, directed by the archaeology department of the University of Harran, excavation and restorations works at the western sections of the town wall were launched. Their aim is to expose a 1 kilometer long section of the some 4 km long ramparts, which according to historical sources were furnished with eight gates and 187 towers in the Middle Ages. The walls, of ancient origin and completely rebuilt by Justinian I in the sixth century, were repaired or rebuilt several times since then. They were finally destroyed in 1272 by the Mongols who evacuated the population and left the town abandoned.

Reference: Hürriyet Daily News, 26 July 2012

The west

side of the town

wall during the excavation and restoration works (© HolyLandPhotos.org)

The west

side of the town

wall during the excavation and restoration works (© HolyLandPhotos.org)07/2012: Hoard of Gold Coins Found in Citadel of Arsūf (Israel)

The ongoing excavations carried out by a team of Tel Aviv University and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority have uncovered a hoard of gold coins inside the citadel of Arsūf, a Crusader town on the Palestine coast conquered in 1265 by the Mamluks after a long siege. The hoard comprised 108 Fatimid dinars hidden in a small broken juglet which was buried below floor tiles. The excavators believe that the cache was hidden immediately before the final capture of the town in 1265.

References: Daily Mail, 11 July 2012; Tel Aviv University News; Video documentary from NTDTV at YouTube

Interior

of the citadel,

northern section

Interior

of the citadel,

northern section The coin hoard (© Pavel Shrago)

The coin hoard (© Pavel Shrago)05/2012: Damage to Medieval Fortified Sites in Syria

- Aleppo Citadel: shelling on gate tower, destruction of Ayyubid iron gates

- Crac des Chevaliers (Qal‘at al-Ḥiṣn): shelling in vicinity, firefights, damage to the mosque and other structures inside the castle

- Hama Citadel: damage reported

- Homs Citadel: tanks and heavy weaponry installed

- Ma‘arrat al-Nu‘mān: citadel bombed

- Qal‘at Marqab: tanks and heavy weaponry installed in the castle

- Qal‘at al-Muḍīq (Apamea): several shellings of the outer walls, bulldozing of walls to create an entrance

- Šayzar Citadel: main door fractured, damage to interior

- Qal‘at al-Raḥba: castle bombed

- Qal‘at al-Šumaymīs: shelters for tanks dug around the base of the castle for the use as a military position

Reference: E. Cunliffe, Damage to the Soul: Syria’s Cultural

Heritage in Conflict,

16 May 2012

Shelling of Qal‘at al-Muḍīq

on 26 March 2012 (© Patrimoine syrien)

Shelling of Qal‘at al-Muḍīq

on 26 March 2012 (© Patrimoine syrien)

Videos documenting damages at Crac des Chevaliers:

Crac1

(10 July 2012), Crac2 (23 July 2012)

See further: Le patrimoine archéologique syrien en danger (Facebook page)

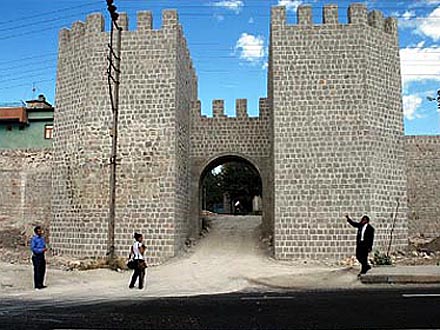

11/2011: West Gate of Melitene (Eski Malatya)Town Walls Restored (Turkey)

In the course of a program to restore the historic town walls of Eski Malatya (Battalgazi), the site of the ancient town of Melitene 12 km north of the modern town of Malatya, the west gate and adjacent wall sections on both sides have been reconstructed. The 2.85 km long walls with 71 towers and 11 gates date back to the reign of Emperor Justinian I who replaced an older Roman fort at this site around 532 CE. During the Middle Ages the town was held by Byzantines, Armenians, Crusaders, Danishmendids, Seljuks, Mongols, and Mamluks. Further restoration works comprise the western section of the town wall.

References: Samanyoluhaber.com; Aksam.com.tr; Restorasyon Forum

Further reading: E. Honigmann, Art. Malaṭya, in:

Encyclopedia of Islam, New Ed., vol. 6, 1990, pp. 230-231; B. Vest, Geschichte

der Stadt Melitene

und der umliegenden Gebiete. Vom Vorabend der arabischen bis zum

Abschluß der türkischen Eroberung (um 600 - 1124), 3 vols.,

(Schriftenreihe Byzanz, Islam und Christlicher Orient, 1) Hamburg 2007

West gate

of Melitene before reconstruction (©

Samanyoluhaber.com)

West gate

of Melitene before reconstruction (©

Samanyoluhaber.com) West gate of Melitene

reconstructed (© Aksam.com.tr)

West gate of Melitene

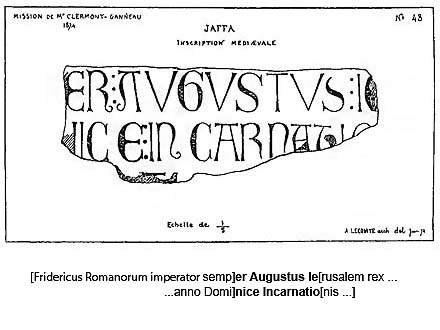

reconstructed (© Aksam.com.tr)11/2011: Arabic Crusader Inscription from Jaffa (Israel)

An Arabic inscription from a building in Tel Aviv has been deciphered recently, revealing significant details. The grey marble fragment bears the name of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and the date "1229 of the Incarnation of our Lord Jesus, the Messiah". Furthermore, all the countries are listed in which he ruled. The unique artistic script used makes it conceivable that a high official or even the emperor himself was responsible for the layout. The fragment seems to be part of a slab which is thought to have been attached to the city wall of Jaffa. It is thus one of the very few Crusader inscriptions in the context of a fortification and the only known Crusader inscription from the Levant in Arabic. This may be explained with Frederick’s favour of Arabic culture. The inscription has a Latin equivalent, which was found in the 19th century and which likewise refers to Frederick II. The Emperor stayed at Jaffa from November 1228 until February 1229 to rebuild the fortifications there.

Reference: LiveScience

Further reading: M. Sharon, A. Shrager, Frederick II’s Arabic

Inscription from Jaffa (1229), in: Crusades 11 (2012), pp.

139-158;

C. Clermont-Ganneau, Archaeological researches in Palestine

during the years 1873 - 1874, vol. II, London 1896,

pp. 155-156 (Latin inscription)

The Arabic inscription of

Frederick II (© Israel Antiquities Authority)

The Arabic inscription of

Frederick II (© Israel Antiquities Authority) The Latin

inscription of

Frederick II

The Latin

inscription of

Frederick II09/2011: Yavneh-Yam/Mīnat Rūbīn (Israel)

Recent excavations at the site, which is located on the Palestine coast south of Jaffa, have revealed that the Early Islamic stronghold occupying the promontory was used by the Fatimids until the first decades of the 12th century. The fortification on the cliff once guarded the small harbour stretching north of it. The place was known to the 12th-century geographer al-Idrīsī as Mākhūz al-Thānī, meaning the ‘second’ harbour, after Ashdod/Azdūd. The discoveries, which include a Roman-style ḥammām, shed new light on the historical topography of the south-western flank of the early Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. The site seems to have marked the northernmost expansion of the Fatimid realm on the coast of Palestine during the first half of the 12th century, possibly until the capture of Ascalon by the Crusaders in 1153. The site is also considered as a place where Crusaders and Fatimids exchanged prisoners.

Reference: EurekAlert!, The Yavneh-Yam Project

The

fortified cliff from NE (© Yavneh-Yam Archaeological Project)

The

fortified cliff from NE (© Yavneh-Yam Archaeological Project) Excavation area showing the ḥammām to the left and

a tower to the right

Excavation area showing the ḥammām to the left and

a tower to the right(© Yavneh-Yam Archaeological Project)

05/2011: The Last Supper in Apollonia (exhibition)

Exactly 746 years after the surrender of the Hospitaller knights of Arsur/Arsūf (ancient Apollonia) to the Mamluks led by Sultan Baybars, the Eretz Israel Museum in Tel Aviv opened an exhibition shedding light on the life inside the citadel during the last days of its existence. When the Mamluks had breached the town walls during the forty-day siege in 1265, its population sought refuge inside the well-fortified citadel. There, according to archaeological evidence, the area where food was prepared and stored had been reorganised due to the larger number of inhabitants. In a former bathroom a large sample of all sorts of dishes and other kitchen utensils was found. The glazed wares from Antioch, Italy and Asia Minor count among the most beautiful of the region. The representative sample allowed to exhibit the "Last Supper" from the final days of the castle.

Reference: Eretzmuseum.org;

Haaretz, 27 May 2011

Further reading: Oren TAL (ed.), The Last Supper at

Apollonia. The Final Days of the Crusader Castle in Herzliya,

Tel Aviv 2011

The dishes of the "Last

Supper" in the castle (© Eretz Israel Museum)

The dishes of the "Last

Supper" in the castle (© Eretz Israel Museum)04/2011: The Battle at Vadum Iacob (Israel)

The team of archaeologists excavating the castle at Jacob’s Ford (Vadum Iacob) has discovered the remains of the Crusader/Templar garrison that defended the castle when it was attacked by Saladin in August 1179. Although its construction was not yet finished, the castle must have been in a well-defendable state. Its strength was admired by Saladin’s administrator, al-Qāḍī al-Fāḍil, who noted that "the width of the wall surpassed ten cubits; it was built of stones of enormous size of which each block was seven cubits more or less; the number of these dressed stones exceeded 20,000." The castle’s strategic importance is underlined by Saladin’s offer of 100,000 dinars to dismantle it. After the capture of the outer ward on the first day, the castle was finally taken on 29 August 1179 by undermining, after a siege of five days. It is estimated that over 800 Crusaders and Templars were killed, many more being taken prisoner. The excavators found well-preserved skeletons showing traces of heavy injuries caused by the fighting. The battle marked a turning point in the history of the Crusader states, as the destruction of this important stronghold paved the way for Saladin’s later achievements against the Crusaders.

Reference: Medievalists.net

Further reading: M. Barber,

Frontier Warfare in the Latin

Kingdom of Jerusalem: The Campaign of Jacob’s Ford, 1178-79,

in: J. France, W.G. Zajac (eds.), The Crusades and Their Sources:

Essays Presented to Bernard Hamilton, Aldershot 1998, pp. 9-22; R.

Ellenblum, Frontier

Activities: the Transformation of a Muslim Sacred Site into the

Frankish Castle of Vadum Iacob, in: Crusades 2 (2003), pp.

83-97

Battlefield at Jacob’s Ford (© Medievalists.net)

Battlefield at Jacob’s Ford (© Medievalists.net) Vadum

Iacob Castle, N

section of outer wall

showing earthquake crack

Vadum

Iacob Castle, N

section of outer wall

showing earthquake crack01/2011: Salamīya and Šumaymīs Castles (Syria)

Excavations in the Muslim castles of Salamīya and Šumaymīs, both located in the governorate of Hama, were conducted to clarify early levels of settlement at these sites. They confirm the hypothesis that both castles were founded in the Ayyubid period. The finds at Šumaymīs comprise a turret, cisterns, coins and potsherds, all from the Mamluk period.

Reference: H. Sabbagh, at: SANA,

26 Jan 2011

See further: J. Bylinski, Exploratory

Mission to Shumaymis –

2002,

in: H. Kennedy (ed.), Muslim Military Architecture in Greater Syria:

From the Coming of Islam to the Ottoman Empire, Leiden 2006, pp. 243-250

Šumaymīs Castle from W (© SANA)

Šumaymīs Castle from W (© SANA) Šumaymīs

Castle, excavation

area (© SANA)

Šumaymīs

Castle, excavation

area (© SANA)10/2010: Haruniye/al-Hārūnīya/Haronia Castle (Turkey)

The castle, also known as Harun Reşit Kalesi, underwent restoration works during the last months, which have significantly altered its appearance. According to tradition it was founded in 799 by the Abbasid caliph Hārūn al-Rašīd. Being one of the strongholds on the Islamic-Byzantine frontier (al-thaghr), it was destroyed, together with its suburb, in 959 by Byzantine troops led by emperor Nikephoros II Phokas. Restored in 967 by Sayf ad-Dawla, the Hamdanid ruler of Aleppo, it was taken over by the Crusaders at the end of 1097. During the following century it changed hands between Crusaders and Armenians and was entrusted by the latter to the Teutonic Knights in 1236, who subsequently had it rebuilt. At the end of the 13th century it was incorporated into the Mamluk empire. The restoration works, scheduled to be finished by the end of this year, aim at the touristic development of the site.

Reference: Castles.nl, HTEKONOMI

The castle from E (© Castles.nl)

The castle from E (© Castles.nl) The castle

from SW showing entrance between gate towers (© Castles.nl)

The castle

from SW showing entrance between gate towers (© Castles.nl)08/2010: Beaufort Castle/Qal‘at aš-Šaqīf (Lebanon)

With the help of the Kuwait Fund for Economic Development, a $3 million project to renovate the castle was initiated. It comprises the consolidation of the walls, archaeological excavations, the reconstruction of the main tower and the castle’s entrances, the landscaping of the surroundings, and the installation of lightings and a drainage system. The castle was left in a state of disrepair when the Israeli forces abandoned it in 2000. They had occupied the site in 1982 using it as a border post. In the Crusader period the castle, located on a ridge overlooking the Liṭānī River at a height of 670 m above sea level, was an important strongpoint in the hinterland of Sidon and Tyre, originally belonging to the Atabeg of Damascus and from 1139 onwards part of the Crusader lordship of Sidon. Conquered by Saladin in 1190 it was in Ayyubid hands until 1240, when it was handed over to the Crusaders by treaty. In 1260 it was sold to the Knights Templar who had to cede it to Sultan Baybars after a short siege in 1268. In the following period the Mamluks used the castle as a part of their coastal defence system.

Reference: TheDailyStar, 30 Aug. 2010

The castle from S prior to the restoration works

The castle from S prior to the restoration works The apron

wall defending the main ward on the south side

The apron

wall defending the main ward on the south side12/2009: Saône Castle/Saladin’s Castle/Qal‘at Ṣahyūn/Qal‘at Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn (Syria)

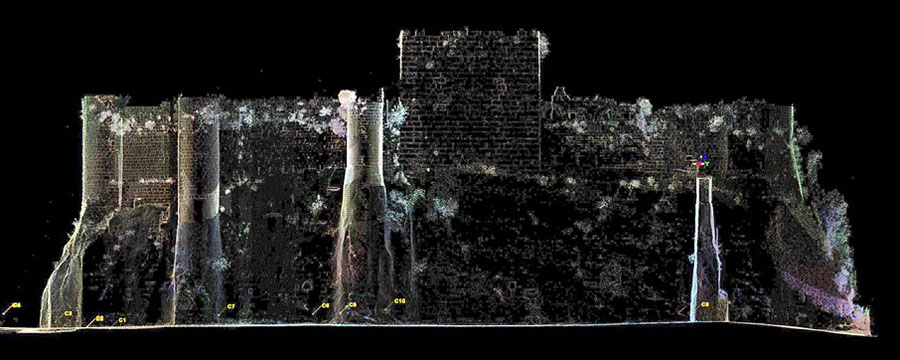

Since 2007 three excavation and survey campaigns were conducted by a conjoint Syrian-French mission (Ifpo/CNRS/DGAMS) at the castle. During the first campaign six soundings were executed in the western bailey, aiming at the collection of data concerning the occupation levels of this area, thus far almost neglected by research. Another objective was the investigation of the vast plateau east of the big fosse, where a suburb, in fact a burgus, had emerged during the medieval period.

During the second campaign in 2008 the ground walls of a Crusader chapel in the lower western bailey were uncovered. Further soundings were executed inside the great tower or keep at the centre of the east front, where parts of the pre-existing Byzantine gate were exposed, and at the two gate towers of the western bailey. Whereupon at the northern one of these, a Crusader construction, the floor of the entrance chamber was exposed, at the southern one, from the Ayyubid period, the bended entrance way was cleared. This campaign was accompanied by a laser scan survey of distinct structures like the castle’s east front towering above the big fosse, the excavated chapel remains and a Mamluk ḥammām inside the Byzantine citadel.

The third campaign in 2009 included further soundings in the western bailey, at the foundations of the Byzantine forewall east of the citadel and in the industrial zone in the south-west section of the main ward, where a large kiln from the Ayyubid or Mamluk period was uncovered. Investigations on the sewage system in the Crusader period and GPS measurements were added.

Reference: IFPO:

Castellologie

Further reading: B. Michaudel, J. Haydar, Le Château de

Saladin

(Saône/Sahyun) et son territoire (vallée du Nahr al-Kabîr al-Shamâlî).

Rapport des missions archéologiques syro-françaises effectuées en 2007

(Ifpo – CNRS – DGAMS), in: Chronique archéologique en Syrie 3

(2007), pp. 303-317; T. Grandin, Introduction

to the Citadel of Salah al-Din, in: S. Bianca

(ed.), Syria: Medieval Citadels between East and West, Turin 2007, pp.

139-180; B. Michaudel, Le Château de

Saladin (Saône/Sahyun) et son territoire (vallée du Nahr al-Kabîr

al-Shamâlî). Rapport des missions archéologiques syro-françaises

effectuées en 2008 (Ifpo – CNRS – DGAMS), in: Chronique

archéologique en Syrie 4 (2008); T. Grandin, The Castle of

Salah ad-Din. Description, History, Site Plan & Visitor Tour,

Geneva 2008

Laser scan image of the

castle’s

east front (© IFPO)

Laser scan image of the

castle’s

east front (© IFPO) Crusader chapel in

western bailey during

excavation

Crusader chapel in

western bailey during

excavation Entrance to Ayyubid tower in

western bailey

Entrance to Ayyubid tower in

western bailey11/2009: Beirut Citadel (Lebanon)

During the last months excavations immediately to the west of the Archaeological Park revealed further sections of the former Crusader citadel. A short stretch of a wall was uncovered showing the same characteristics as the tower excavated further east in the 1990s. These are big rusticated ashlars, ornated with mason’s marks, alternating with ancient columns used as headers. A further wall, running parallel to it, was uncovered at a distance of 6 m. Both walls were built over in the Ottoman period. It is tempting to assume that the latter was the town wall and that the gap between the walls was once taken up by a moat. The continuation of the works may clarify these findings.

West wall of

Crusader

citadel

(right),

Ottoman pier (left)

West wall of

Crusader

citadel

(right),

Ottoman pier (left) Wall opposite

citadel west

wall

Wall opposite

citadel west

wall09/2009: Margat Castle/Qal‘at al-Marqab (Syria)

The renovation works at the castle were accompanied since 2006 by excavations and surveys, conducted by a Syro-Hungarian team (Syro-Hungarian Archaeological Mission). The results of its work were presented now at the 5th Military Order Conference at Cardiff University. The most important discovery was made inside the castle chapel last year. There, on the walls of the nave, hitherto unknown medieval frescoes were detected, displaying motifs of the Last Judgement. The scenes, which were drawn by a western artist at the end of the 12th century, depict heaven (south wall) and hell (north wall). Their style and iconography seem to be unique. Further discoveries were made concerning the sewage system, the defensive elements, the food consumption of the occupants and the layout of the pre-Hospitaller castle. Additionally, a survey of earthquake damages was conducted.

Reference: Medieval Hungary Blog, 20 Oct 2010;

M. Kázmér, B.

Major, Distinguishing damages from two

earthquakes—Archaeoseismology

of a Crusader castle (Al-Marqab citadel, Syria), in: The

Geological

Society of America, Special Paper 471 (2010), pp. 185-198,

doi:10.1130/2010.2471(16)

See further: B. Major, É. Galambos, Archaeological and Fresco

Research in the Castle Chapel at al-Marqab: A Preliminary Report on the

Results of the First Seasons, in: P. Edbury (ed.), The

Military

Orders, Volume 5: Politics and Power, Aldershot 2012, pp. 23-48; G.

Buzás, The Two Hospitaller Chapter Houses at al-Marqab: A

Study in Architectural Reconstruction, in: ibid., pp. 49-64;

I. Kováts, Meat Consumption and Animal Keeping in the Citadel

at al-Marqab: A Preliminary Report, in: ibid., pp. 65-74

Fresco

on north wall of chapel

depicting hell

Fresco

on north wall of chapel

depicting hell Fresco

detail: the damned

Fresco

detail: the damned Hall

adjoining the inner

gate:

state of

1994

Hall

adjoining the inner

gate:

state of

1994 Hall

adjoining the inner

gate:

state of

2009 after renovation

Hall

adjoining the inner

gate:

state of

2009 after renovation Main wall next to

outer gate, after repointing

Main wall next to

outer gate, after repointing Latrine

chamber at first floor level of main ward, after clearing

Latrine

chamber at first floor level of main ward, after clearing09/2009: Rumkale/Qal‘at ar-Rūm/Hṙomgla Castle (Turkey)

The first phase of a restoration project at Rumkale, run by the Gaziantep Provincial Culture and Tourism Directorate, is now completed. It comprised conservation works at the eastern and western entrances of the castle. The project is scheduled for another five years. Nevertheless, the site will be opened for visitors in 2010. The next objective is the restoration of the walls and galleries of the castle. This impressive stronghold on the river Euphrates, founded by the Byzantines or Armenians, lost much of its topographic setting after the flooding of the Birecik Dam reservoir in 2000. Located on a precipitous spur shaped by the confluence of the Merzumen Cay and the Euphrates, the water level now reaches the foot of the castle walls. The extant ruins are mainly Armenian, with considerable Mamluk enhancements of the fortifications. Between 1151 and 1292 the castle has been the seat of the Armenian Catholicos and the site of an important monastery.

Reference: Today’s Zaman, Rumkale Restoration Project

Further reading: H. Hanisch, Die Klosterfestung Hromklay am

Euphrat, in: H. Hofrichter (ed.), Beiträge zur

armenischen Baugeschichte, 1, Kaiserslautern 2001, pp. 135-166; id., Hromklay.

Die armenische Klosterfestung am Euphrat. Eine baugeschichtliche

Untersuchung. Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung der Fotodokumentation im

Vorarlberger Landesmuseum, Bregenz 2002; A. Stewart, Qal‘at

al-Rūm/Hṙomgla/Rumkale and the Mamluk siege of 691AH/1292CE,

in: H. Kennedy (ed.), Muslim Military Architecture in Greater Syria.

From the Coming of Islam to the Ottoman Period, (History of Warfare,

35) Leiden 2006, pp. 269-280

The castle

from N (© Halfeti

tekne turları)

The castle

from N (© Halfeti

tekne turları)08/2009: Balatunus Castle/Qal‘at Maḥālba (Syria)

The walls of the castle, previously much overgrown, were recently cleared from shrubs, followed by conservation measurements executed on behalf of the Syrian Department of Antiquities. The extensive refortification works of the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods are now much better comprehensible. These concern mainly the entrance complex to the south of the lower ward with a double bended access way and three gates and the reinforcement of the upper ward by a massive glacis at the entire stretch of its south face against the lower ward. Similar to the nearby castle of Saône/Ṣahyūn the older Byzantine and Crusader structures are now clearly discernible.

The castle from SW

The castle from SW The entrance complex to the S

The entrance complex to the S The castle’s upper ward and

its glacis from SE

The castle’s upper ward and

its glacis from SE07/2009: Petra and Šawbak (exhibition)

An exhibition at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence/Italy from 13 July to 11 October, entitled Da Petra a Shawbak. Archeologia di una frontiera, shows results of the archaeological investigations of the University of Florence at the Jordanian sites of Petra and Šawbak during the past fifteen years. These investigations focused on the medieval fortifications of al-Ḥabīs and al-Wu‘ayra (the Crusader Vaux Moise) in Petra and the castle of Šawbak (Crusader Montréal). The key element of the exhibition is the diverse role that the frontier plays in the understanding of historical processes in the respective region. The time frame covered spans from antiquity to the Ayyubid and Mamluk epochs. Additionally, an international conference was held at Florence from 6 to 8 November 2008 to discuss this particular issue.

For more information see here.

Šawbak Castle from W

Šawbak Castle from W Šawbak

Castle, masonry

stratigraphy displaying façade of south church

Šawbak

Castle, masonry

stratigraphy displaying façade of south church© Petra ‘Medievale’ – Shawbak Project

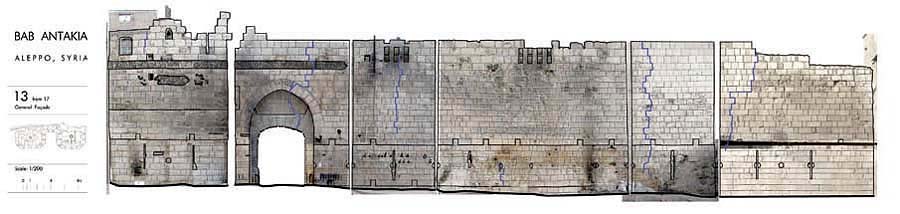

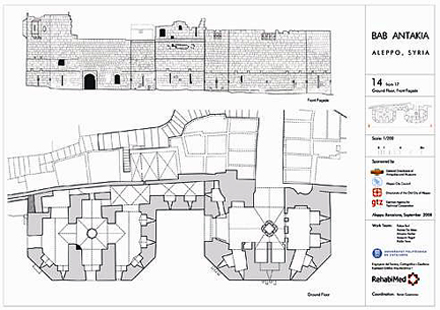

05/2009: Antioch Gate (Bāb Anṭākiya) and City Wall of Aleppo (Syria)

On behalf of the German Agency of Technical Cooperation (GTZ) a workshop was organised where members of the RehabiMed team presented the results of their studies and investigations on the city wall around Aleppo’s Antioch Gate. The main objective of this meeting was to provide guidelines for the rehabilitation of this section of Aleppo’s city wall, which is concealed by shops and a wall built under the French Mandate. The recommended measures comprised the removal of the French Mandate wall and the restoration of the historic wall. The investigations at the gate revealed that it had several predecessors over a long period. The extant structure dates from an Ayyubid rebuilding in 1245, whereas the upper floor was remodeled in the late 14th century. After the 16th century the gate lost its military function when shops were built around the structure, one of the towers turned into a khan and the upper floors used as dwellings. As at many gates of the period, the two towers, measuring about 25 by 15 m, fulfilled different purposes. The south tower contained the (bended) passage while the north tower took over defensive functions, in particular the protection of the gateway. The Antioch Gate counts among the best preserved examples of the kind, conceivable in its full monumentality after restoration.

For more information see here.

Aleppo,

Antioch Gate, elevation of

façades (©

RehabiMed)

Aleppo,

Antioch Gate, elevation of

façades (©

RehabiMed) Antioch Gate, rear elevation

and ground plan (© RehabiMed)

Antioch Gate, rear elevation

and ground plan (© RehabiMed) Antioch Gate, south gate

tower after restoration

Antioch Gate, south gate

tower after restoration01/2009: Town Wall Fortification at Jaffa (Israel)

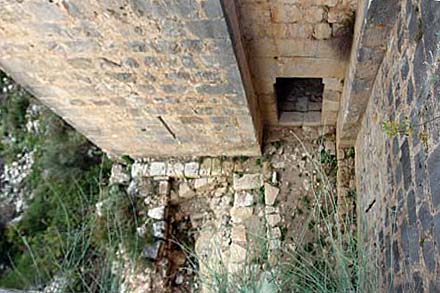

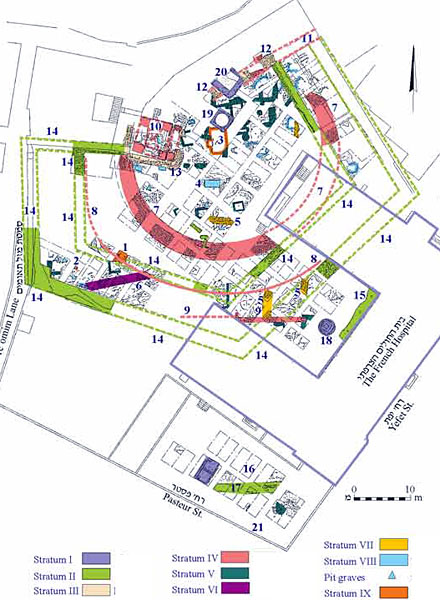

Excavations during 2007 and 2008 at the French Hospital compound have revealed new evidence for the fortification of the southern section of the town wall of Jaffa in the late Crusader period. The site is located south of the ancient tell, which was occupied by the medieval citadel. The remains of an Ottoman bastion, incorporated into the western perimeter wall of the hospital, were always a conspicuous testimony of the town limit in this period. Earlier hypotheses, postulating that they coincide with their medieval predecessor, could now be corroborated. The excavations in the courtyard of the hospital brought to light a massive circular glacis, founded on bedrock and built of ashlars in regular courses to an extant height of 3 m, and the foundation trench of the adjoining city wall north-east of it. The glacis was of a slightly oblate circular shape and had a diameter of more than 35 m. It was surrounded by a moat with a maximum upper width of 14 m, by a bottom width of 6-7 m. The sloping counterscarp was lined with soil and rubble. At the western part of the glacis a square structure consisting of a groin vault on four massive pillars was exposed which was founded on bedrock. It was assumed that it served as foundation of a tower/gate or the base of a bridge. This glacis must have been the base of a massive bulwark once having defended the endangered landside of the town. The pillared structure may indicate the existence of an access to the town at this point. A gate to the south, the ‘Ascalon gate’ is recorded in the sources. Beyond the moat remains were uncovered, which might have belonged to a forewall. The archaeological evidence and the shape of the glacis leave no doubt that this ensemble was the work of king Louis IX of France, who was located there from May 1252 until June 1253. Whereas the Ottoman fortifications of the 18th century, which were destroyed by Napoleon in 1799, used the 13th-century line of the town wall, the mighty pentagonal bastion from the early 19th century more or less enclosed its medieval predecessor, thus illustrating identical needs in fortification over times and cultures.

Reference: A. Re'em, Yafo, the French Hospital, 2007-2008.

Preliminary Report, in: HA-ESI 122 (2010) 24/11/2010

Further reading: D. Pringle, The Churches of the Crusader

Kingdom of Jerusalem. A Corpus, Vol. I: A-K

(excluding Acre

and Jerusalem), Cambridge 1993, pp. 264-267; Benjamin Z.

Kedar, L’enceinte de la ville franque de Jaffa, in:

Bulletin monumental 134 (2006), pp. 105-107

Glacis at south section of

town wall (© IAA)

Glacis at south section of

town wall (© IAA) Pillared structure on top of

glacis (© IAA)

Pillared structure on top of

glacis (© IAA) Detail of glacis (© IAA)

Detail of glacis (© IAA) Excavation plan: red =

Crusader (mid-13th c.), green = Ottoman (© IAA)

Excavation plan: red =

Crusader (mid-13th c.), green = Ottoman (© IAA)12/2008: Citadel of Arsūf (Israel)

The citadel from S

The citadel from SFor more information see here.

10/2008: Maṣyāf Castle (Syria)

Comprehensive restoration and consolidation works, which began in 2000, were completed recently. They were executed by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) within the framework of a larger programme to revitalise historic citadels in Syria, in cooperation with the Syrian General Directorate of Antiquities. These works provided new insights into the building history of the site. The remains of the earliest fortification, a Byzantine castle from the 10th/11th century, could be established, as well as the refortification campaigns of the Ismailis during the 12th and 13th centuries. The most impressive structure from this period is the polygonal apron wall encasing the south front of the Byzantine castrum on top of the ridge. The clearing of a system of rock caves adjacent to the main stairway revealed a ḥammām of the same period, with walls decorated with mural paintings (see picture below). The destructions caused by the Mongol attack in 1260 were determined, just as the refortification works carried out by the Mamluks after sultan Baybars had seized the castle from the Ismailis in 1270.

More information: AKTC

Historic Cities Programme for Syria.

Further reading: H. Hasan, Introduction

to the Citadel of Masyaf, in:

S. Bianca (ed.), Syria: Medieval Citadels between East and West, Turin

2007, pp. 181-214; id., The

Citadel of Masyaf.

Description, History, Site Plan & Visitor Tour,

Geneva 2008

The castle from E

The castle from E The ḥammām

below the inner

castle gate

The ḥammām

below the inner

castle gate03/2008: Montfort Castle Project (Israel)

A survey project directed by Adrian Boas of Haifa University was launched at Montfort Castle (Qal‘at al-Qur‘ayn) two years ago. During the first two seasons of the project the upper ward of the castle was surveyed, including a photographic survey of the extant remains. The latter had been uncovered by a team of the Metropolitan Museum of New York in 1926. In the 2007 season further exploration methods like aerial photogrammetry and 3-D laser scans were introduced. In 2008 the survey will extend down to the northern and western slopes covering the castle’s outer ward. In the future, archeological soundings and the development of the site for tourists are planned. The castle, built by the Teutonic Knights in 1226 and abandoned after its conquest and destruction by Mamluk sultan Baybars in 1271, has never been resettled or quarried for building material. This offers unique opportunities for reconstructions.

Reference: A. Boas,

The Montfort

Castle, a New Survey, in: HA-ESI 120 (2008)

26/03/2008

Further reading: A. Boas, R. Khammisy, The Teutonic Castle of

Montfort/Starkenberg (Qal‘at Qurein), in: Hubert Houben

(ed.), L’Ordine Teutonico tra Mediterraneo e Baltico, (Acta Teutonica,

5) Galatina 2008, pp. 347-361

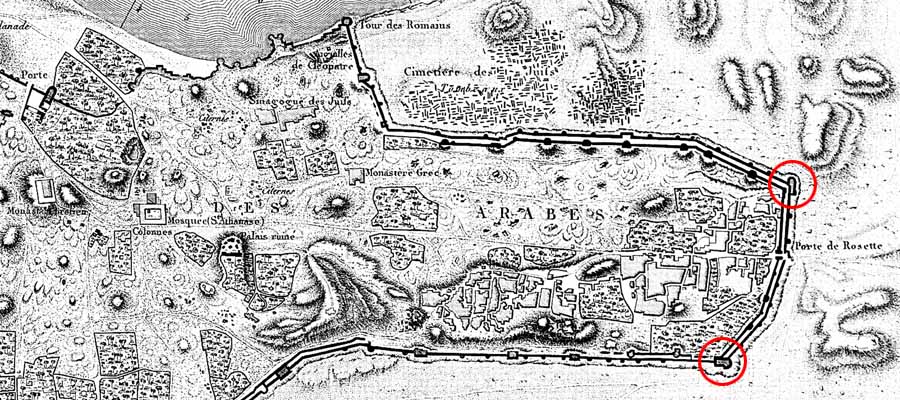

02/2008: City Wall of Alexandria/al-Iskandarīya (Egypt)

In the framework of the excavations at the late-Mamluk Citadel of Qāit Bāy a study on the medieval fortifications of Alexandria was conducted on behalf of the Centre d’Études Alexandrines. The medieval city walls were built by the Tulunids in the late 9th century, after the ancient walls had been pulled down in 875. Sultan Saladin had them reinforced due to the threat of Crusader attacks, who laid siege to the town in 1167 and 1174. During the Mamluk period (13th to 15th centuries) they were repaired and additionally protected by several small forts, positioned around the two harbours. The fortifications consisted of a double wall, c. 9 km long, with towers at regular intervals, surrounded by a moat. This made Alexandria to one of the strongest fortified cities in the Eastern Mediterranean. In the 19th and early 20th centuries the fortifications were almost completely dismantled. Only two towers, once the corner towers of the east section of the wall circuit, are preserved.

Reference: K. Machinek, Les

fortifications de la ville d’Alexandrie depuis le Moyen Âge jusqu’à nos

jours, at: CEAlex

Further reading: I. Muhammad Hussam al-Din, The

Fortifications of Alexandria during the Islamic Period, in:

Bulletin de la Société archéologique d'Alexandrie 45 (1993), pp.

153-161

Map of medieval city walls,

east section (Description de l’Égypte, 1823)

Map of medieval city walls,

east section (Description de l’Égypte, 1823) Remains of NE

tower (© CEAlex)

Remains of NE

tower (© CEAlex) Remains of SE tower (©

CEAlex)

Remains of SE tower (©

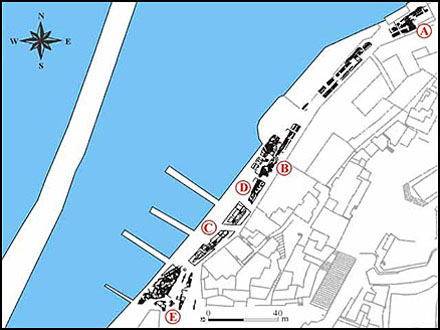

CEAlex)12/2007: Sea Wall and Harbour Fortress at Jaffa (Israel)

During the second half of 2007 a salvage excavation was conducted in the harbour area of the Old Town, where five trenches along the harbour promenade were opened. The earliest of the five strata uncovered was dated to the Crusader period. Immediately west of the Greek Orthodox Church compound (Area A on the plan) a c. 22 m long wall was exposed, with a preserved height of c. 2.3 m above sea level. The slightly slanting outer face shows medium-sized ashlars laid in regular courses. Sections of this wall, with a thickness of c. 2.5 m, have already been excavated in 1978. In 1997 an excavation along the sea front of the Armenian monastery revealed a further wall of almost the same build, running parallel to the former and founded on solid bedrock. Stratigraphical analysis indicates a dating to the Crusader period. These finds, however, do not yet allow to relate them to the recorded Crusader period building campaigns of 1100, 1191, 1228, or 1252.

In the southernmost trench (Area E) remains of a massive construction were exposed, interpreted as a part of a Crusader fortification located at the western end of the harbour. Bottom courses of a talus, c. 2 m thick and built of massive kurkar stones, were exposed, belonging to the north wall of the fortification. South of it a wide room with a plaster floor was uncovered. This ensemble served as a foundation for the later Ottoman harbour fortress. The fortification protruded out into the sea and may well have been an advanced or detached bulwark of the citadel on the hill site of ancient Joppa to the east of the harbour. Fortifications delimitating and protecting harbours are a common feature of Crusader sea ports.

Reference: E.

Haddad,

Yafo Harbor. Preliminary Report, in: HA-ESI 121

(2009) 25/8/2009

See further: H. Ritter-Kaplan, Jaffa Port, in: HA

65/66 (1978), pp. 25-26 [Hebr.]; M. Peilstöcker, La ville

franque de

Jaffa à la lumière des fouilles récentes, in:

Bulletin monumental 164 (2006), pp. 99-104

Excavation

plan (© IAA)

Excavation

plan (© IAA)

Crusader harbour wall in

area A (© IAA)

Crusader harbour wall in

area A (© IAA) N wall

of harbour fortress in area E (©

IAA)

N wall

of harbour fortress in area E (©

IAA) Talus

of harbour fortress in area E (© IAA)

Talus

of harbour fortress in area E (© IAA)

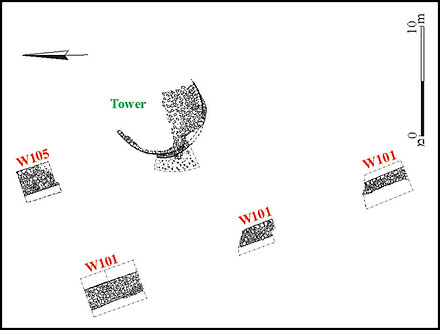

08/2007: Crusader City Wall at Tiberias (Israel)

New evidence for the western city wall of Tiberias in the Crusader period was found in a trial excavation conducted in August 2007 on HaGalil Street in an area near the Municipal Park. Three sections of a wall 1.85 m wide were uncovered, with evidence for a moat west of it. The wall, which may have been erected in the late 11th/early 12th century, cuts through a stratum dated to the Early Islamic period. Further east, another wall 2.35 m wide parallel to the former was uncovered. The absence of construction remains between the two walls indicate that the c. 10 m wide space between them could have been a moat. Notwithstanding the limited scope of the excavations, these findings lead to the assumption that at least the western section of the city wall was of the concentric type. The scheme displayed here seems to have consisted of a main wall and a forewall, each accompanied by a moat in front it.

Reference: A. Mokary, M. Hartal,

Tiberias.

Final Report, in: HA-ESI 122 (2010) 17/11/2010

Further reading: Y. Stepansky, Das kreuzfahrerzeitliche

Tiberias:

Neue Erkenntnisse, in: M. Piana (ed.), Burgen und Städte der

Kreuzzugszeit, Petersberg 2008, pp. 384-395

Excavation plan (© IAA)

Excavation plan (© IAA) Wall W101, looking W (© IAA)

Wall W101, looking W (© IAA)